Case 52

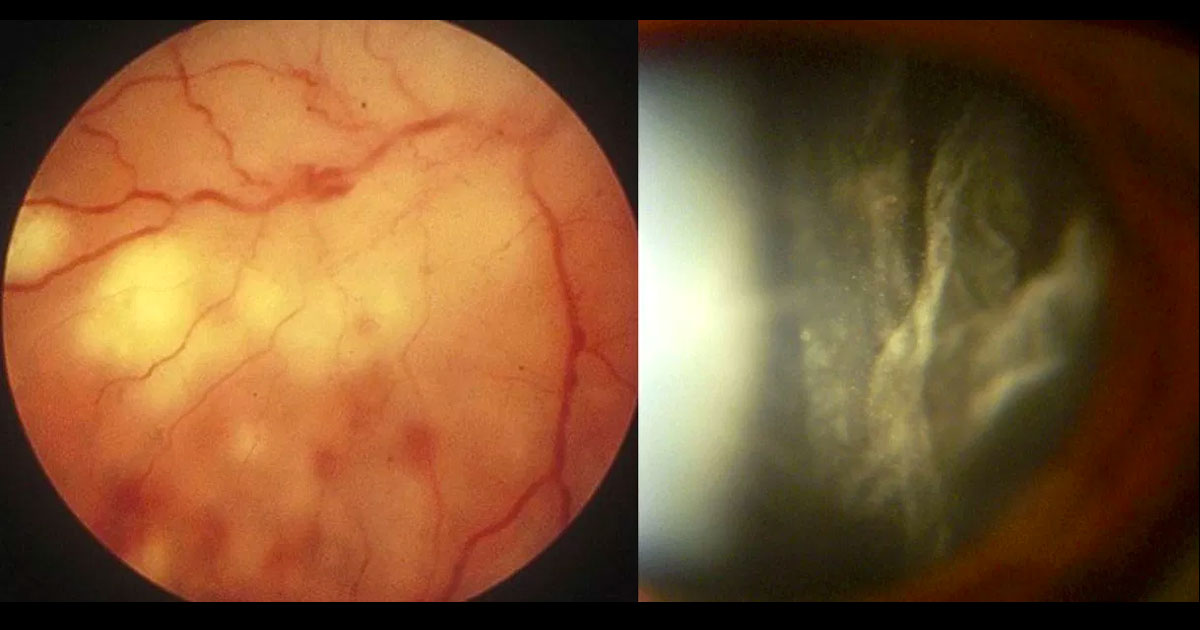

Figure 1. Colour fundus photograph of the right eye demonstrates white necrotic retinitis with intraretinal haemorrhages (left image). A moderate vitritis was present (right image).

Author: Raj Chalasani Editor: Adrian Fung

A 54-year-old male was referred with reduced vision in his right eye.

Case history

A 54-year-old male was referred from his optometrist with a 2 day history of blurring of vision in his right eye associated with floaters.

Best corrected visual acuities were 6/18 in the right eye (OD) and 6/60 in the left eye (OS). Intraocular pressures were 15 in both eyes. Examination of the anterior segments revealed 2+ cells in the right eye and a quiet left eye. Examination of the posterior segments revealed vitritis associated with an area of retinitis with surrounding intraretinal haemorrhages in the right eye (Figure 1), and geographic atrophy in the left eye with no active inflammation.